While COVID-19 is the only thing many people are thinking about right now, hurricane season is officially only a few weeks away, and we shouldn’t let the pandemic draw our attention from this fact.

The pandemic will add another layer of complexity to the responses of teams across the Caribbean and the Southeastern US. What are some of the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and other disasters mixing, and what can people do to prepare for natural disasters that occur during this pandemic?

2020 Models and Predictions

The first important item to address is that the pandemic will end eventually, which means teams will only have to adjust their responses through this year and possibly 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic will most likely only collide with the 2020 hurricane season, which means we can get a rough estimate of how often and how drastically teams will have to transform their usual response plans.

Experts are predicting that the 2020 hurricane season will be more active than normal. The absence of an El Niño and warmer ocean waters will help tropical storms form; researchers at Colorado State University predicted 18 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes will develop this year in an early April 2020 report (major hurricanes are category 3, 4, and 5 storms).

The same report by the CSU researches stated that there’s a 69% chance of one major hurricane hitting the U.S. coastline. What this report suggests, then, is that there’s a strong chance a major hurricane strikes somewhere along the US coastline. Responders need to prepare for this possibility and more. Lesser hurricanes and tropical storms are still violent storms, and can force people into shelters, destroy infrastructure, and impact a community in significant ways.

Every year, the Southeastern US and Caribbean have to endure these storms. These areas also experience other disasters on occasion. Floods, tornadoes, wildfires, earthquakes, and other events are all possible, some more likely in certain areas than others. Because all of these disasters can coincide with the pandemic, it’s good for us to start thinking about the impacts of combined disasters, and how teams can adjust to these unique conditions.

How COVID-19 Will Influence Disaster Response

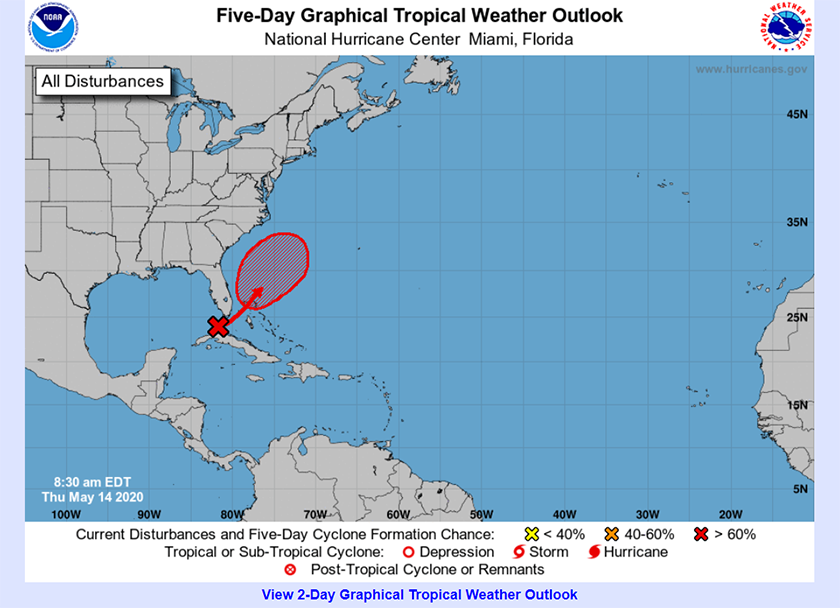

At the time of publishing, the first tropical storm appears to be developing, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has started to track.

â€

By the looks of it, concurrent disasters will be something we have to manage in 2020. We won’t be able to avoid these scenarios. What does this mean for the people affected by disasters in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Typically, infrastructure is damaged in some way during disasters. Events like hurricanes tend to knock out power and the infrastructure that delivers electricity to homes, businesses, and other organizations.

Normally, there’s a rush and a collective effort by utilities across the country to help turn the power back on, via a process called mutual aid. The logistics of mutual aid can be complicated; this operation often requires the affected utilities to support visiting crews with shelter and other needs.

We’re all familiar with social distancing now, and this practice will creep into operations like mutual aid. During the pandemic, if infrastructure is damaged at a large scale, it’ll most likely take longer to restore than it has in the past. Utilities will have to enforce and practice social distancing and other preventative practices to ensure the safety of their workers. Expect this to happen across the board.

The pandemic will affect shelters for the displaced the most. Keeping everyone safe and healthy will be the biggest concern, and it will require substantial changes to the plans of those responding to a hurricane (or other natural disasters).

Controlling COVID-19 at Shelters

To slow the spread of COVID-19, towns, cities, and counties have banned large gatherings of people and implemented social distancing policies. Shelters, by their nature, go against these ideas, but they will be necessary if and when a major disaster, like a hurricane, hits an area.

We’ll need to adapt shelters and implement practices that help prevent the virus from spreading throughout the shelter.

Shelters will need to allot more space for each person staying in their facilities to adhere to social distancing guidelines. Those in charge of shelters can also ensure everyone wears a mask or face covering while they’re in the shelter and that shelter guests are educated on policies and procedures; tell them how they can protect themselves, such as limiting their contact with others within the shelter. (You can find the CDC’s recommendations for individuals staying at disaster shelters during the pandemic here.)

Screening processes will also go a long way, and may allow administrators to isolate potentially infected individuals from the healthy. Regular cleaning, especially within high traffic areas, can also help curb the virus within the shelter.

Planners and emergency managers should anticipate needing more shelters than they normally do as well because space will be so limited. They may even want to consider using hotels to shelter displaced people.

Responding to COVID-19 and Disasters

For the next year, and some time after, we’ll have to factor in COVID-19 when we plan for large scale disasters like hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, floods, and more. The virus and its ability to spread adds a new layer to responding to these disasters and how we help the people affected by them. Doing so will require careful consideration and effort, but will ultimately help those people already hurting from disasters.